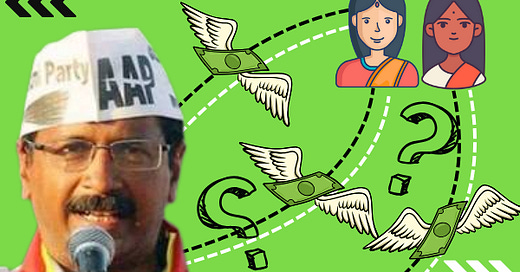

AAP’s recent cash transfer scheme comes as no surprise in light of the upcoming Delhi Elections. It is often a common political tactic by parties to attract and secure voters by promising lucrative schemes. The AAP Mukhya Mantri Mahila Samman Yojana offers cash transfers of ₹1,000 to all women over the age of 18, with a promise to increase it to ₹2,100 if the party comes to power. Framed as a solution for women’s empowerment, the scheme guarantees a fixed lump sum for financially disadvantaged women. However, several questions arise when we analyse it from an economic and social perspective. How successful are cash transfer schemes, and what is their financial impact? Are direct cash transfers better than investments in long-term social infrastructure? Let us break this down in this blog.

The cash, the incentive, and the Moral Hazard problem

Cash transfers are often opted as a direct policy for redistribution. The process is simple and much more certain in reaching its target audience. The cash amount is transferred to the accounts of the registered beneficiaries, who can decide what to use it for. It is an easier and more personalised way of helping women who need financial support. Its biggest impact at this level is providing a sense of having one’s own money as a woman and not relying solely on your husband.

However, the question of finances and impacts becomes important when talking about policies. Cash transfers work in a funny manner when scheme beneficiaries keep increasing, as people who might not need them also try to avail such benefits. Thus, the benefit of this scheme also attracts women who do not necessarily need this financial assistance, and just want some freebies. The benefit of this policy to them isn't betterment, but luxury. The individual reactions to cash transfer policies make them more financially demanding. As the government insures people against financial shortcomings, it encourages those who do not need it to seek such benefits. For example, the daughter of a well-off family might also opt into this scheme, and yet the additional money would have no desired impact for empowerment. And so, the costs ever so keep increasing as sneaky rich aunties who probably wouldn't benefit off this money keep registering because the appeal of an extra ₹1000 is admirable. With the ever-increasing cost, the financial burden of cash transfer programs often overpowers, making them difficult to run for the long term.

And the promise of empowerment?

As we jump on to analysing the impact of this policy, we must understand the society in which it is being implemented. In a society where men are considered superior, what guarantee do we have that an extra ₹1000 in a woman’s pocket will bring about a desired change? There is no surety that the woman will use this money for herself: an average mother might spend it on her kids or everyday items like groceries. Financial standing is important, yes, but not when it fails to bring about a CHANGE. What is needed more urgently is long-term policy to change societal schemas regarding women. This quick fix to attract women voters does not deliver what it claims to. Low-earning or house-working women continue to live under their male counterparts, subjected to dominance and even violence from them. Even working women continue to face an ever stronger glass ceiling at work. Instead of solving any of these more important problems, such yojanas only bring us to vote bank appeasement and a minimal impact on the social standing of women. At max, it brings with itself a small sense of financial freedom for women. But, is that enough?

What is it that women empowerment would need?

The capital of the world’s largest democracy remains, like the rest of the country, inefficient in dealing with the plight of women. The many years of progress have yet to secure true equality between both genders; as women continued to be treated as secondary. What women empowerment requires is more than freebies for appeasement- it requires long-term policies and investments that can rid people of a negative mentality towards women. It would require greater effort from the government to be able to bring about grassroots changes that create a more equitable society.

Long-term investments in social infrastructure, like better schools, curriculum, and civic amenities, hold much more potential to improve the state of women in India and in Delhi overall. Better accessibility to institutions holds more power in breaking stereotypes against women than providing them cash schemes. Provide the low-strata women with clean water and sanitation, with affordable education, with flexible vocationality, and watch them change their worlds themselves. That is not to say that the government has not introduced schemes on the same; it obviously has, but the diversification of schemes diversifies effort as well, and schemes are left stranded and under implemented. The government should focus on firstly, having schemes with more impact on the condition of women, but secondly, reorganizing and implementing existing schemes. Multiple schemes under the Delhi government, though well intended, have yet to achieve their desired impact because of a lack of implementation. Policies like providing inexpensive sanitary pads have left female students in a lurch due to clashes over vendors. Too many schemes create a web of ineffectiveness and delayed implementation, and optimizing the schemes might be much more consequential.

What should the government focus on then?

Cash transfers may be more direct and affirmed in their impact, but that impact is too small scale for it to bring about an actual change in society. Long-term policies might require constant administration and supervision but hold the potential for changes to facilitate women empowerment. I believe in a society grappling with deeply ingrained ideas and thoughts about men and women, and their stature, it is only long-term policies that can bring about change. Such transfer programs can only be a side aid to people, never the central focus of development.

The problem of finances

The AAP government has been notorious for providing its people with top amenities, often free of cost. The government is currently proposing programs providing free electricity, water, education in government schools, and free bus rides for women along with support programs for pujaris, autowalas, senior citizens, and businesses. On top of that, the government also proposes an unconditional cash transfer scheme for women. While all of these are good-intentioned, the toll they take on the finances is a concern. Delhi is headed towards a significant departure from a fiscal surplus of ₹3,231,19 crore in 2013 to reveal a likely deficit of ₹6,565 crore crore in 2025. In a report by RBI, the sharp increase in fiscal deficits has been highlighted, with states' fiscal deficit to GDP (FD/GDP) projected at 3.2% for the FY25 budget from the estimate of 2.9% in FY24 provisional estimates. In such a scenario, it is wise to focus more on programs that bring about actual change and impact, rather than cash transfers to women with the vague promise of empowerment. Optimizing its schemes to focus more on those with higher impact will benefit the government in the long run.

Alas, a grand race of vote-bank appeasement….

But, of course, what is politics without a little bit of healthy competition? Kejriwal’s announcement of this scheme has been followed by a similar if not exaggerated scheme by all other parties: AAP, BJP, and INC each trying to one-up the other by increasing the cash amount or increasing incentives. This has started a rat race of women appeasement between parties, each one determined to win over the 71 lakh women voters of the capital by offering more and more incentives. However, while the impact of cash transfers remains inconsequential for women empowerment, it certainly has a few damaging impacts on the narrative about women. So many unconditional transfer schemes make women look like freeloaders in a system already determined to declare them secondary. Thus, enough of freebies, instead let us look forward to stronger implementation and impacts from our upcoming governments.

Great Insights,

However do you think the governments should also provide the exact metrics they would track post the release of such schemes to understand if it was a success or failure?

Would this bring in more accountability?

Insightful read!!